Creuza de Mä | Fabrizio De André’s Sea Changing Milestone

When he first listened to Creuza de Mä, the chief administrator of the Italian label Ricordi suddenly felt disheartened. “Let us hope we’ll manage to sell at least a few copies in Genoa” he sighed. Creuza de Mä was the latest work by Fabrizio De André, one of the most complimented songwriters in Italy. It was winter 1984, and De André was already a legend. Ever since he first gained the recognition of his audience in the mid-60s, he was renowned for his fingerpicked songs, and his sophisticated, often political lyrics. But Creuza de Mä was far away from anything he had done before — so far as to be disorienting. For starters, it combined guitars and violins with ouds, bouzoukis and mandolas. Was this not to be enough, it was written in the old dialect of Genoa.

When it came out, Creuza de Mä seemed anything but commercial. But one year later things appeared to be quite different. “Goodness knows how long it’s been since we were present at such a manifestation of a unanimous consent in the field of pop music. We needed Creiiza de Mä (sic!)”, wrote the Italian newspaper La Stampa on January 20, 1985.

On that day, the album had won a gold disc. Defying any market logic, an apparently unsellable album had become one of De André’s greatest successes, and to an unprecedented extent. Not only did it sell “a few copies in Genoa”, but it even won over international audiences, eventually becoming a full-blown cult. With its Mediterranean sound and its linguistic oddity, it stands nowadays as a milestone of World Music.

On the wave of World Music

The release of Creuza de Mä wasn’t De André’s first step out of his comfort zone. Over the years, the French songwriting arrangements of his early days had left room for other sounds. An uncommonly private artist, he had never played live in front of an audience until 1975. But when he decided to step onto a stage, he did it with style. Thanks to the collaboration with the progressive rock band PFM, his classic tracks took on a whole different tune during the tours. This experience made him conscious of the expressive possibilities of a well-researched, complex orchestration. In this way, all through the 70s, he enriched his compositions with rock and blues elements. Yet none of these developments was remotely comparable to the revolution embodied in Creuza de Mä. This stands as true for De André as it does for the 80s global music landscape.

In 1984, the concept of “world music” or “ethnic music” was in its infancy. Throughout the previous decade, musicians had begun incorporating traditional elements from around the world in their compositions. Meanwhile, with the diffusion of reggae, Latin American music, South African tunes, and the influence of Francophone West Africa, the value of alternative musical languages became suddenly obvious. In Italy, there had been a few attempts to ride the wave. In 1974, Lucio Battisti released Alma Latina, a colorful combination of Pop music and Latin American sounds. But while the shift was already happening, Creuza de Mä had something unique, and it’s not just about its Mediterranean sound. Before its release, no pop musician had gone so far as to write an entire album in a local language, let alone a dead one.

The sound of the Mediterranean

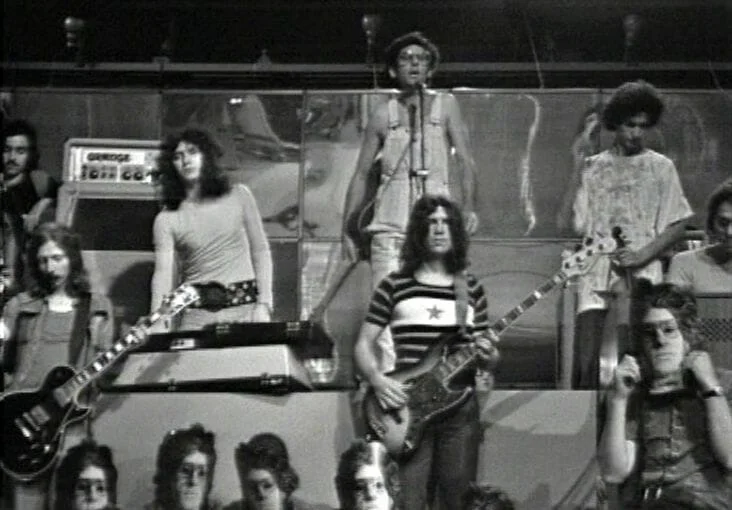

It goes without saying that Creuza de Mä was a tricky undertaking. Yet, when asked what moved him to produce it, De André gave a simple answer. “Since we inhabit the Mediterranean, we live by it, we thought it was worth starting to make Mediterranean music. Employing Mediterranean instruments…” he said in an interview with RAI. Sitting on his right was a dark-haired guy in a white shirt. The man was Mauro Pagani. A former member of PFM, Pagani was one of the most talented multi-instrumentalists in Italy. He had been researching Mediterranean music for a while, and he is the brains behind all the orchestration.

“I took care of the musical part, while Fabrizio worked on the lyrics. He was very brave: he was famous for his lyrics and suddenly he published an album you couldn’t understand a single word of,” Pagani declared in a 2014 interview.

But the choice to write in the old dialect of Genoa was perfectly consistent with the aim of the album. Throughout the Middle Ages, Genoese had been a lingua franca in maritime trade. It was spoken all around the Mediterranean basin. “…When we had to look for a language that could be a blend of all Mediterranean idioms, I felt that Genoese was it” recounted De André.

Of seamen, soldiers and whores

Behind those mysterious, ancestral-sounding words, De André weaved the stories of the most picturesque characters in the basin. They are adventurers, outcasts and prostitutes: De André’s lifelong favorite subjects, but placed on the seaside. Most of the songs are about Genoa. That is the case of the title track, Creuza de mä, which recounts the hardships and the pleasures of the seaman’s life. Other tracks take place on faraway shores. Jamin-a, for example, was inspired by De André and Pagani’s trips to Africa and the Middle East. It is about a prostitute working in harbors: the tired seaman’s companion.

As De André explained, “Jamin-a is not a dream, it is rather the hope for a truce. A truce from the possibility of a Force Eight gale at sea, or even a shipwreck. […] Jamin-a is the partner in an erotic travel, that any seamen hopes, or rather demands to meet in every harbor”.

Even the third track, Sidún, has an Arabian setting. One of the most evocative tracks of the album, it was inspired by the 1982 Lebanon war. It is about a man who finds out that his child died under the wheels of a tank. De André described it as a metaphor for the civil and cultural death of Lebanon under the bombings.

A bridge over the seas

By writing Creuza de Mä, De André gave voice to the loves, the pains and the hopes of all the marginalized inhabitants of the Mediterranean basin. He found and displayed the common roots of apparently faraway worlds. It is one of the greatest accomplishments of the album. Through its atavistic and yet familiar sounds, it inspires the listeners to embrace the beauty of otherness. In this sense, it is a sort of invitation to travel.

“The sea parts and unites peoples and continents. When it parts them, I would say it stimulates dreams, imagination. When it unites them — that is, when one begins traveling — it’s a continuous contact with reality.”

Creuza de Mä’s success was itself borderless. David Byrne was enthusiastic about it, and described it as one of the most important releases of the 80s. The German filmmaker Wim Wenders is a fan as well. He first got acquainted with De André through this album and suddenly became a fan. Today, he describes him as “one of my favorite musicians on the planet.”

Forty years after the concept of world music first gained popularity, the criticisms of its implications have become numerous. Does it make sense to put all non-westerner music in the same pot? According to David Byrne, it is “a way of relegating this ‘thing’ into the realm of something exotic and therefore cute.”

Here lays the importance of Creuza de Mä. With its incomprehensible lyrics and its local sounds, it spoke to global audiences, and it did it loudly.

You can stream Creuza de Mä on Spotify.

Tag